MANUDOS

MANUDOS

The country still smelled of freshly pulped coffee, the houses were arranged close to the train tracks, as if the Plums River had washed them there by chance. At the end of each passenger car, just before the anchorage area, there were small open balconies where passengers would travel.

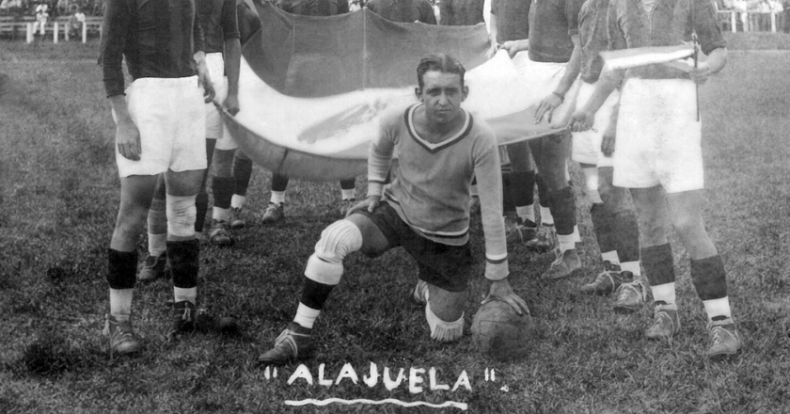

A group of boys from Alajuela were heading to the Caribbean to work for a few weeks.

Inside the carriage, tempers were flaring—not so much over politics or philosophy, but because of the recent championship match played the day before, where Liga Deportiva Alajuelense had faced Club Sport Herediano just a few days earlier.

—Liga’s the champion!—shouted Toño as some guys boarded the carriage at the Heredia province station.

One of them stared into the distance for a while, and when the train started moving, he turned to his friends and, as if it were something they were also thinking about, he said to them:

—La Liga had 17 points, and Heredia only 14… They won by a mere 3 measly points… and we all know they got those points because they stole a penalty from us.

Toñito knew he was speaking for the people of Alajuela, so he turned to his friends and, feeling a poisonous anger, he said to them out loud and without hints:

—Penalty, my foot!— He adjusted his hat, his face red with indignation, though no one could tell if it was from the heat of the train or the argument. —How is that not a penalty? They shoved him like they were toppling a sack of coffee. That’s a foul here and in heaven!”

The Herediano player, seeing that it no longer made sense to hide, removed his own friends from the area and made his way towards the Alajuelense players to face them:

—It’s just that you guys are always up to something. If you can’t win with soccer, you win with theater. I remember that clear penalty, and he took it himself.

Darío, the liveliest of the group, jumped in laughing:

—Hey, bighead, who told you we wanted to talk to you?

—Anyone shouting ‘Liga’s the champion’ here in Heredia is talking to me.

His friends stepped in to ask him to calm down, but he only stopped when the train attendant—a skinny guy who smoked a lot and worked little—showed up, puffing smoke and silently flashing the machete at his belt, not as a threat but as a distinguished request for caution. They backed off, but Darío, stubborn as a pig in a pen, threw more fuel on the fire:

MANUDOS

—You know what? —The ladies rolled their eyes at the boys’ stubbornness— . Heredia might have the better team, but Alajuela has passion. That’s why we’re champions, dammit!

There was a commotion on the train. The attendant raised his hands and asked for silence, but no one paid any attention to him. So Darío took the opportunity to say:

—Look… We gave them a good slap in the face in the Ochomogo War and they haven’t learned their lesson.

—We Heredia people gave you a good slap in the face in the War of La Liga. You had to ask Saint Joseph for help.

The attendant got in the way:

—You’re sister provinces. Back in the day, when the people from Alajuela didn’t have a church, they’d go to mass in Santa Bárbara de Heredia.

—Oh, don’t talk so much!—said Toño angrily—.Though you’re right. We built an oratory just so we wouldn’t have to see you.

That made everyone let out a mocking “oooh.” Then, almost by chance, they fell silent. The attendant celebrated that they had finally stopped the nonsense when suddenly they heard:

—They gave you the championship.

—Here we go again with the same old nonsense… Enough! This is too much trouble.

Things only calmed down when the train arrived at the next stop in Heredia, and they got off there. Toño leaned toward Juancho and said quietly:

“Calm down, Darío. I have an idea for how we’ll get back at them for not accepting that we won that championship fairly… Look, what we’re going to do is…” —As they continued their journey to the Caribbean, they came up with a plan.

A week later, on another trip to the Caribbean, the Alajuelenses had a plan that they carried out, orchestrated by Toño. They had noticed that the women hung their clothes in their patios that were very close to the railway line, so they went quietly to the balconies of the wagon and from there, taking advantage of a turn of the train, they stretched out their huge, rough hands to steal the underwear that the women had hanging.

As if it were booty, they showed off what they had stolen, dancing against the wind like a little flag. Other people from Alajuela heard the rumor and dared to do the same. First with a pink bra, then with a high navy blue thong. After that, the clotheslines in Heredia became the target.

The people of Heredia didn’t give a damn, and they would go around doing unpaid rounds at the times when the train passed. They would cut chilies from the coffee bushes and make sure that nobody put their hands out of the window. And even so they couldn’t prevent the robberies from continuing. But Heredia was not a peaceful town.

The women from Heredia, fed up with their clothes ending up as trophies from wagon to wagon, gathered in a large house next to Nicolás Ulloa park. There they planned their revenge. They covered black underwear with an equally black ink, the same ink that notaries used for their seals.

As the sun went down the train passed by as always. Toño, who didn’t waste a trip, hung onto the balconies again and, as if by magic, caught hold of the clothes in mid-flight, between laughter and screams.

“I’m going, I’m going!” —whispered Darío, and in an instant, his hands reached out quickly, grabbing a couple of items of clothing with the certainty that no one could stop them.

They noticed her hands were damp and stained, but everything seemed to be following its usual course. Until they arrived at Heredia’s central station.

There were the people of Heredia, waiting. Men, women, children, and even the local police. The officers entered and asked everyone to show their hands. In their search, they found a wall with the imprints of huge hands, and the bar with occasional smudges where they had been holding on.

—Yeah, they got their hands dirty… look at the prints, they’re a bunch of manudos. It’ll be easy to recognize them. The culprits had their hands shoved in their pants pockets, crouched down among the crowd.

When the policeman approached them, they both ran off and jumped over the balcony railing and ran through the streets of the town:

“There go the manudos!” —shouted a woman, pointing at the blackened hands of Toño and Darío, who were running, looking for a coffee plantation to hide in.

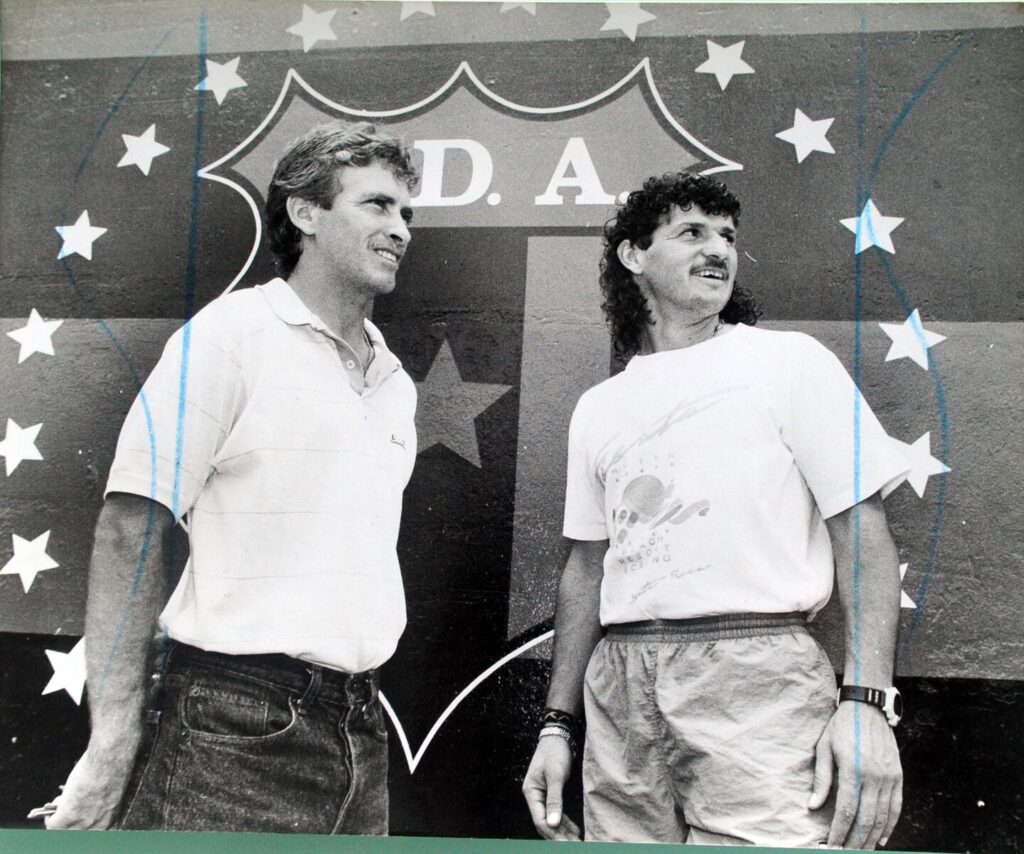

After that, clothes kept disappearing, but less and less each time—everyone was afraid of getting caught. However, the nickname “manudos” was born right then and there, and it stuck with the same firmness as the fiery and pointless rivalry that keeps us entertained between provinces.

MANUDOS

Previous article Gaza / Israel: notes from Costa Rica on the encirclement of justice that is gradually closing in on Israel

Navigate articles