Juan Santamaria, he did go to school…

Juan Santamaria, he did go to school…

The first time I heard the possibility that Juan Santamaría had died of cholera was during a genealogy course, when the name of the hero appeared on the death lists of the 1856 campaign and it was recorded that he had died as a victim of the epidemic. I shuddered at the thought that this could be the most disastrous hoax in history.

My teacher, a member of the Costa Rican Academy of Genealogical Sciences, acted with the utmost naturalness after that comment and continued his class. He began to explain the socio-racial reality of Costa Ricans, and in this way he moved from topic to topic, at great speed, hurried to meet the objectives of the day.

I raised my hand to ask for the floor and to take up the subject again. I wanted him to expand if I had been lied to all these years, if Juan Santamaría was a farce, but I remained silent when he replied:

That would take us to a whole new level and if you want we can include it, but in the second stage of the course, the program is already set. For now I need to continue talking about the descendants of Juan Vásquez de Coronado.

My thoughts returned to that madness as I returned home, but I was soon distracted by the daily hustle and bustle. A year later, Juan Santamaría returned to my life when, sitting in the library in Alajuela, one of my classmates said to me:

The truth is that of the contingent of volunteer soldiers in the 1856 campaign, there were five Juan Santamaría, let’s say, that was a very, very common name. As common as saying Rodríguez, Vargas or Rojas today. Moreover, in our culture, biblical names have always been the most used, and Juan was perhaps the most typical.

The army was made up of around 2000 soldiers, so it was very logical that it was repeated and there were many volunteers from Alajuela.

I had that feeling again of feeling cheated. Actually, what did that Juan Santamaría do, the one who really burned the inn, well, if he really burned it, I don’t know. But you understand what I mean, I’m talking about the one from the civics books.

I realized that during the war of 1856, the priest José Francisco Calvo joined the troops, yes, a priest in the middle of the war. His role was to give moral support to the soldiers, and also when they died to help them reach the afterlife without sin, so that they could finally be received by the most renowned saints in all their pomp, as they deserved. So, that man of peace and cassock set off with the troops as soon as they left San José on March 4, 1856, together with President Juan Mora, to face the filibusters. Some of his belongings must have included the book of deaths, ink and a pen, as well as a rosary, a crucifix and the few other things he needed to survive in that warlike adventure.

As they passed through the villages they were warmly welcomed by the peasants and the indigenous people who collaborated with their harvests for the cause. The heavy carts loaded with ammunition, cannons and all kinds of equipment were pushed up and down the avocado hills, what a brutal effort. They crossed rivers and mountains until they reached Puntarenas, from where they sailed across the Gulf of Nicoya and the waters of the Tempisque to land at Bebedero de Cañas. From there they continued their journey overland once again to Liberia and Santa Rosa. A doctor, the priest, illustrious foreigners and women also traveled in this caravan, people who deserved to be in the history books but were forgotten. They managed to cook rice, beans, bananas, tortillas, coffee and whatever else they found along the way to feed the soldiers. They washed clothes on the riverbanks and stopped to prepare food.

When death came, whether from natural causes or in battle, the priest had to write in his own handwriting in the death book the name, day, place of death, place of origin and the cause of death of the soldier. He must have opened his book for the first time on March 20th, when Juan Mora’s army took the filibusters at the Hacienda Santa Rosa by surprise and several Costa Rican soldiers were killed. That day, in fact, was Maundy Thursday, and the priest must have linked the success of the campaign to the divine presence on that day, as the attack lasted only 15 minutes because the filibusters, seeing their defeat, immediately took the road to Nicaragua.

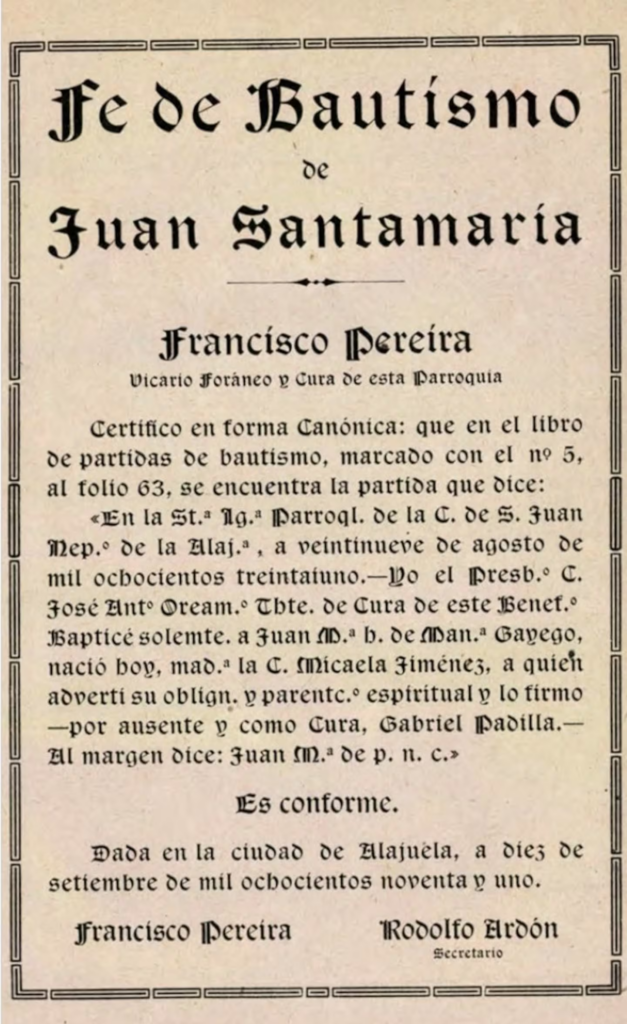

With the army’s morale high, Juan Mora and the rest of the Costa Rican army set out for Rivas, Nicaragua with the consent of the government of the neighboring country whose interests were the same, to get rid of the presence of William Walker. In April, the inn was burned down by a 23-year-old drummer boy named Juan Santamaría from Alajuela. Juan’s mother was Manuela Carvajal and she was also known as Manuela Gallego or Santamaría, as at that time it was common to use the surname of one of the parents or even of the grandparents. In fact, Juan’s grandfather was from Heredia and, according to genealogy studies, it is said that his name was Martín Santamaría.

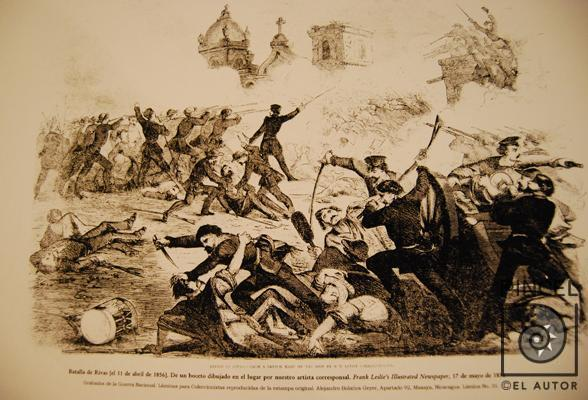

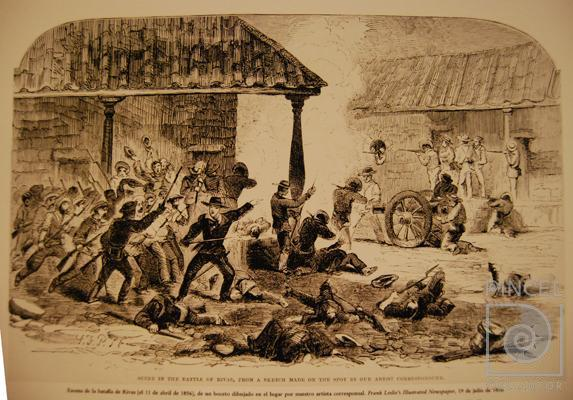

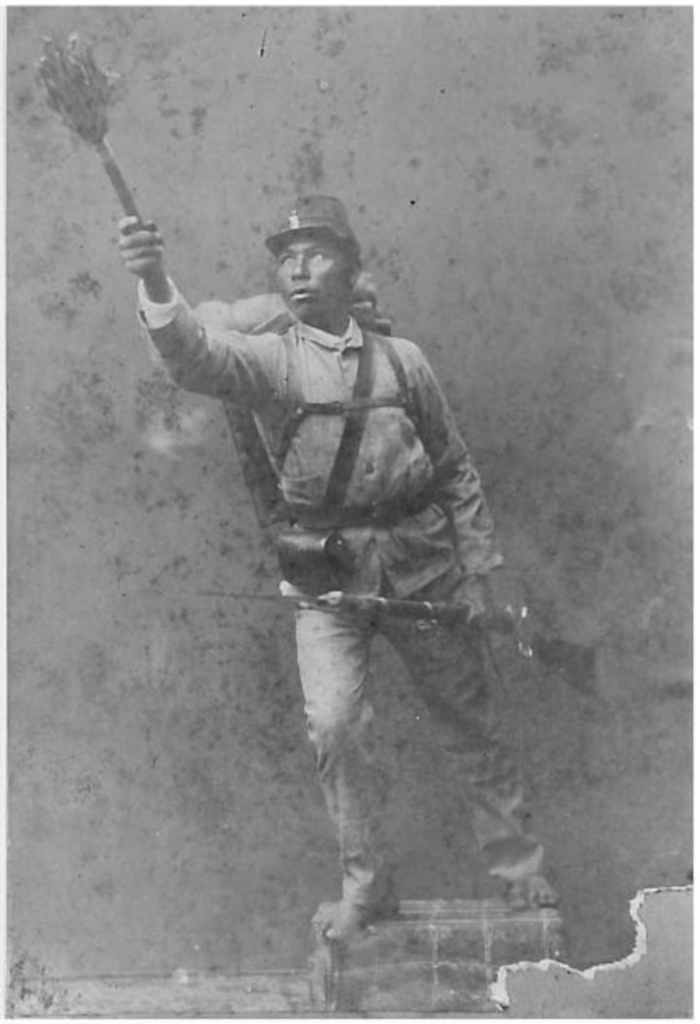

The Costa Rican army was based in Rivas, William Walker had confidential information and attacked the Costa Ricans at 8:00 in the morning, taking them by surprise. The lieutenant from Cartago, Luis Pacheco Bertora, tried to burn the inn, but failed and was unharmed. Joaquin Rosales, from Nicaragua, also fought in the Costa Rican ranks but was defeated before reaching the inn. Juan Santamaría was selected for this task at a critical moment, after two failed attempts by two other soldiers, and he managed to burn down the inn with his torch, although he was shot dead.

Meanwhile, in the rain of bullets, the priest took care of the wounded together with the doctor and the women. In the hustle and bustle of the emergency, he forgot to keep a full list, running from one place to another with so many dead around him that he was called away in that moment of agony. In their last words they asked him to take messages to their mothers, their wives, their daughters; it was not the time to take out his inkwell and his book. That night was full of horror; in the darkness he prayed for the deceased and could not sleep among so many wounded people.

By April 12th, the filibusters had left Rivas, Nicaragua and calm had returned amidst a bloodbath, hundreds of mutilated corpses scattered in the streets and injured people screaming in pain. The priest thought he had woken up in hell. They made the decision to bury the bodies in mass graves. There is no certainty about the exact figure. It is estimated that between 300 and 750 Costa Ricans died that day. How many names must have been overlooked and who could recognize those bodies amidst the smell of blood? Days later in Rivas, while they were still feeling that sadness, the cholera epidemic took its toll on the survivors. So the suffering increased, as did the number of deceased, of course.

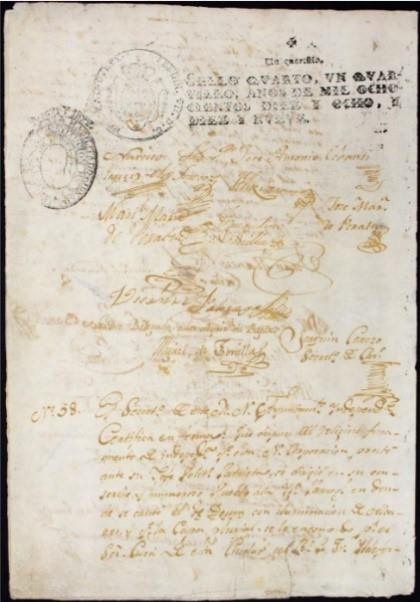

When some historians set out to look for the name of Juan Santamaría in these documents to consolidate their research, they found the other Juan Santamaría, the one who died of cholera. They also became suspicious because the document of the priest Juan Francisco Calvo was neat and clean, it did not look like an object of war, but rather an office document.

The existence of Juan Santamaría is based on documents such as the pension application by his mother, Manuela Carvajal, then the mention of his name in an official speech by José de Obaldía in 1864, and then another petition from Santamaría’s mother, requesting an increase in pension. But the document in which Juan Santamaría was born was an article by Álvaro Contreras, “An anonymous hero”, which circulated in 1883 in a local newspaper in Alajuela, published in Tambor. But they have also found in the National Archives, in the list of those killed in action between April and May 1856, the name of Juan Santamaría as having died in action.

I recover my hero. It feels like I can look him in the eyes in the beautiful bronze statue, placed in the square with the lightning torch pointing to the sky. Standing in front of my colleagues in the Alajuela library, I start to hum:

Juan Santamaría nació en Alajuela,

Lyrics: Araceli E de Pérez Music: José Castro C.

tan pobre vivía que no fue a la escuela.

Pero dentro de él sintió un gran valor y

llegó al cuartel de simple tambor.

Se marchó a la guerra lleno de emoción y

con una tea incendió el Mesón.

Esto fue en Abril un día como hoy y

de hazañas mil esta es la mejor.

My companions, they smile cheerfully, and the person next to me comments:

They found his name on a teacher’s lists and in a student census that had been taken at the time.

Author

Elizabeth Chango

Navigate articles