From Colony to Freedom: The End of the Colony

The End of the Colony.

Other countries such as Mexico and Peru, the Spaniards lived a lazy life thanks to the riches of the country and the work provided by the indigenous people. In Costa Rica, due to the lack of mines, communication routes, commerce and the scarce population, they were reduced to great poverty, and had to cultivate the land with their own hands to avoid starvation. Poverty was such that in the early eighteenth century cocoa circulated as currency due to the scarcity of silver.

Subsistence economy

Cartago, seat of the Governors and capital of the province, in 1723 consisted of about 70 adobe and tile houses, a main church and three chapels; there was no doctor, no pharmacies, and no grocery stores. However, we must not confuse that poverty with misery, since in the colony there was no misery, and it can be assured that the cupboards of the Costa Ricans were never fuller than at that time. If there was no sale of foodstuffs in Cartago, capital of the province, it was precisely because they were not needed.

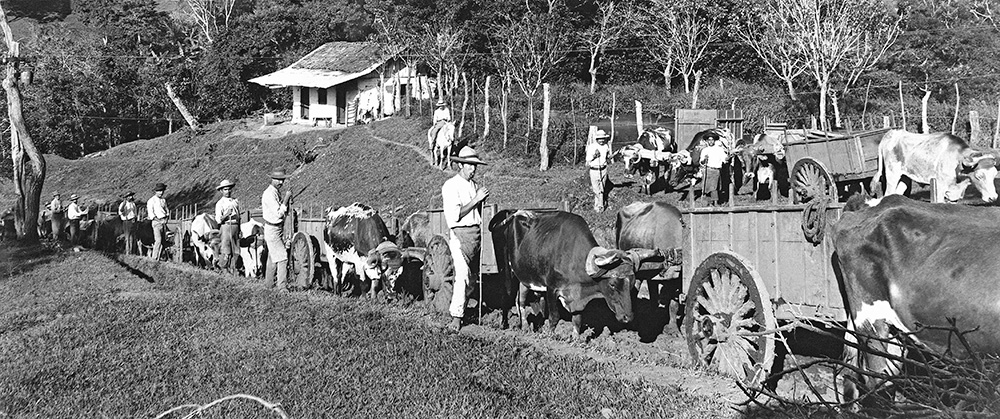

The simple farmer, a human product of the colony, lived quietly and dedicated to the cultivation of his plot of land, which provided him with corn, beans, yucca, wheat, tobacco, sugar cane and many other products necessary for his subsistence. In addition, he had a few head of cattle, pigs and horses that provided him with meat, milk and transportation. It was a typically homemade economy.

When another document mentions that in Cubujuquí, a town that barely had 200 families, there were more than one hundred sugar mills, this shows that each family had its own sugar cane plantation and its own sweet production. As for the fact that in Cartago the houses were made of adobe and tile, it was simply the fashion of the time. Poverty in the colony consisted mainly in the lack of luxury, money and lack of progress. There were no means of communication, commerce was of little volume and industry was almost non-existent.

The impact of coffee on economic transformation

It was with the introduction of coffee, at the end of the colony and the beginning of independence, that the country’s panorama changed completely. With the sales of coffee abroad, money began to circulate, luxury, silks, cashmeres, jewelry and household goods, among others, appeared. Progress began, but at the same time misery arose. The farmer sold his land to more enterprising people who formed large coffee plantations, becoming a laborer or wage earner, leading to misery.

During the colonial period, there was no movement of rebellion against Spanish power in Costa Rica. The economic life, weak and limited, did not allow the formation of powerful classes to defend their interests against the Spaniards. The property, as mentioned before, was distributed, and each family had its own land to cultivate what it needed. This economy did not allow the creation of large urban centers. The small human centers that emerged, such as Cartago, Heredia, San José and Alajuela, were small villages of slow and simple life. These reasons explain why there was not an environment conducive to political concerns.

The end of the colony: The transition to independence

Costa Rica did not feel the arbitrary oppression of the Spanish authorities that was cruel and intolerable elsewhere. The Spaniards, although with some pretensions, did not make themselves felt in colonial life, and the Creoles enjoyed great freedom and peace, without being interested in the progress of the colony.

Our colonial authorities, especially in the last years, were good men, kind patriarchs. Don Tomás de Acosta governed from 1797 to 1810. During the governorship of Don Juan de Dios de Ayala, from 1810 to 1819, the residents of San José decided to create in 1814 an educational center by public subscription, known as the Casa de Enseñanza de Santo Tomás. Don Rafael Francisco de Osejo, a native of Nicaragua, was brought in to direct it. Philosophy, Grammar, Theology, Morals, Reading and Writing were taught. Before this center of higher education, the rural culture had only basic schools with simple learning tools: La Cartilla and El Catón.

Navigate articles