The “declassification” of secret documents by the United States 50 years after the 1973 Chilean military coup: brief notes

The recent “declassification” of secret documents by the United States 50 years after the 1973 Chilean military coup: some reflections.

Text written by Nicolas Boeglin, Professor of Public International Law.

Chilean military coup

“Si olvido

mis hijos cargarán la ira

Si no olvido

le pongo nombre a la justicia

y a ellos

les nacerán alas”

Valeria Varas, Futuro (poem) quoted in her play Mi Paulina, San José, Edit. Gráfico Litho, Tinta en Serie No. 34, 2016, Scene 8, p. 31.

Chilean military coup

In the days leading up to the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the 1973 military coup in Chile, the United States officially decided to “declassify” documents held in reserve for five decades: see The Progressive Magazine story and RFI story of 9/09/2023.

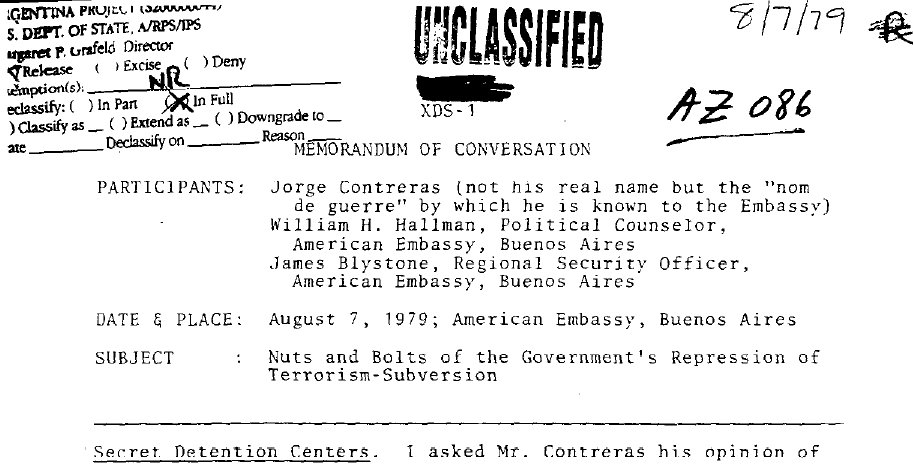

These are only two new documents that come to add to many others released in past years by some US administrations, and registered on this site of the George Washington University: an extensive research program dedicated to Chile – which is not limited only to the declassification of US documents – and which has this link with a wealth of information.

In its official communiqué, the U.S. Department of State referred to this declassification, stating that:

The Biden Administration has sought to be transparent about the U.S. role in this chapter of Chilean history by recently declassifying additional documents from 1973, as requested by the Chilean government.

(véase texto en español difundido el 11/09/2023)

We will see in the following lines that the aforementioned “transparency” of the United States would merit a much more sustained and consistent effort.

Always very sensitive documents, 50 years later

Although the international press has highlighted the reasons why this 1973 coup d’état shook Latin America and the international community in general (see, for example, this note from the BBC of the same 11/09/2023 which we recommend reading), the involvement of the United States widely documented since then (and assumed in part by the current US administration), is an aspect that would deserve to be added (for example, to the four points mentioned in the aforementioned BBC article).

It is not superfluous to refer our esteemed readers to this 1970 handwritten document authorizing the overthrow of the future president of Chile if he were to take power (see link when declassified in 2020, stating that: “Fifty years after it was written, Helm’s cryptic memorandum of conversation with Nixon remains the only known record of a U.S. president ordering the covert overthrow of a democratically elected leader abroad”).

This other note reads that the most recent declassification of documents by the United States in August 2023 was due to express requests made by the current Chilean authorities:

After withholding this document in its entirety for decades, the CIA finally released the September 11, 1973, PDB today in response to a formal petition from the Chilean government of Gabriel Boric for still secret records as the 50th anniversary of the coup approaches. The CIA also partially declassified a second PDB, dated September 8, 1973, which erroneously informed President Nixon that there was “no evidence of a coordinated tri-service coup plan” in Chile and said that “should hotheads in the navy act in the belief they will automatically receive support from the other services, they could find themselves isolated.

The two PDBs are among the most historically iconic of missing records on the September 11, 1973, military coup because they contained information that went to President Nixon as a military takeover that he and his top advisor Henry Kissinger had encouraged for three years came to fruition

asjduiay

For the information of our readers, the two aforementioned quotations refer to the text in English elaborated by the research program on declassified documents of the George Washington University, which situates in time and analyzes each of the documents released in recent years by the United States. In this video produced by Chile Visión (see link), several days in 1970 and later are “reconstructed” by this research program, from declassified cables, documenting and revealing the content of key meetings that explain the involvement of the highest authorities of the United States.

Chilean military coup

However, the request made by Chile in 2023 to the United States probably concerns many more documents still in the possession of the U.S. administration, which has limited itself to declassifying only two of them. And… what is still to wait for the declassification of the rest of the files in the United States?

In a recent interview conducted on September 12, 2023 in the United States (see full text), we read that for one of the George Washington University researchers who knows the subject best:

There are other secrets that we want to get out. The Chilean government has asked the Biden administration for a special declassification diplomacy gesture for this 50th anniversary. So far, only two documents have been declassified. There are many more that have been asked for, that hopefully, you know, at some point will come out.

The release of official documents in the right to truth: lights and shadows

From the perspective of public international law, it should be specified that there is no obligation for a State to release documents from the reserve in which they are held because they are considered “sensitive“. Each State has a national archival system with internal reports, data and records of various kinds: its highest authorities are the ones who decide to keep them out of the public domain or to disclose their existence.

This is how Panama had to wait 30 years since the 1989 US invasion for the United States to finally agree to release a large number of classified documents (see note from El País– Spain of 12/17/2019).

Chilean military coup

In other cases, police or military documents and reports are “found“, such as the so-called “archives of terror” discovered in a house in the town of Lambaré in Paraguay on December 22, 1992 (see publication of the Paraguayan Supreme Court of Justice and interesting video of the moment in which a Paraguayan judge accompanied by the press asks to enter the house to verify the presence of these archives and seize them).

The data found in the archives discovered in Paraguay in December 1992 made it possible to document a large number of cases in different parts of the Southern Cone. It also allowed the Italian judiciary to convict on July 8, 2021 14 people for the death of 43 people, victims of the Condor Plan with dual nationality (namely 6 Italian-Argentines, 4 Italian-Chileans, 13 Italian-Paraguayans and 20 Uruguayans): see note in Italian by the Italian NGO CILD. Similarly, in 2010, the French justice system convicted those responsible for the disappearance of four French citizens in Chile (see note in Le Monde of 18/12/2010).

What Paraguay observed in December 1992 does not imply that the Paraguayan state apparatus looked favorably on what happened in Lambaré. In a very complete interview with this same Paraguayan judge, conducted in 2019 (see link), we read the following:

The next day, in the morning, the President of the Court (José Alberto Correa) called me, who had been called by the President of the Republic, General Andrés Rodríguez, asking him that these documents should not be aired. But that was already impossible. The citizens, the people, were already owners of those documents, from the moment they were found. From that point on, it was a road of no return.

Chilean military coup

Returning to the case of Chile, the iron will of its current authorities to obtain the release of classified documents by the current U.S. administration is to be welcomed.

Note that in its official communiqué of August 25, 2023 the U.S. Embassy in Chile felt compelled to outline the criteria used to decide (or not) to release documents, without considering that 50 years have already passed since the episode to be clarified, by stating (see full text) that:

The declassification of documents is a complex, multi-agency process in which the U.S. government takes into account numerous factors, including national security, protection of sources and methodology, and other risks and benefits of disclosing specific information. With these factors in mind, the U.S. government completed this declassification review in response to a request from the government of Chile and to allow for a deeper understanding of the story we share.

Finally, it should be pointed out that in terms of “soft law“, resolution E/CN.4/RES/2005/66 of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights – today called “Human Rights Council” – adopted by consensus in 2005, at the initiative of Argentina (its text is available on the web), and entitled “The right to the truth“, limits itself only to indicate that:

5. Encourages States to provide the necessary assistance to the States concerned in this regard.

Right to truth vs. concealed truth: some developments in public international law

The absence of a legal obligation between two States to hand over information held by one to the other, related to human rights violations committed in the past, in no way prevents us from having a very different dynamic when we are interested in national and international courts in the implementation of the so-called “right to the truth“.

In this case, it is the victims’ collectives, family members and human rights associations that have asserted before their own authorities or before the national courts (and if these have ruled against them, before the international courts) this right, which applies to all victims of past exactions committed by state authorities (whether against them or against one or more of their loved ones).

In this regard, a very complete report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on the Right to the Truth, published in 2014 (see text) details the scope of the right to the truth in the Inter-American system for the protection of human rights. The long list of cases heard by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights at the end of an academic article published in Colombia in 2008 (Note 1), gives an idea of the guidelines that the jurisprudence of the Inter-American judge has been setting in this regard, and this since its first judgments against Honduras in the late 1980s.

It is noteworthy that the significant advances observed in Latin America in terms of the right to truth have not yet permeated the judicial system in Spain: the first exhumation of the body of a victim of Franco’s regime ordered by the justice system was achieved in 2016 thanks to a request from… the Argentine justice system (Note 2).

Chilean military coup

From a historical point of view, we read that the right to truth finds its origins in the situation in Chile when it was examined in the 1970s by human rights bodies within the United Nations, when it was stated that:

As noted above, the first precedent in the United Nations system is the work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Situation of Human Rights in Chile. In its Seventh Report to the General Assembly, this Ad Hoc Working Group raised the issue of the right of relatives of disappeared persons to know the fate and whereabouts of the disappeared. It reaffirmed the right of family members to know the fate of the disappeared as established in international humanitarian law and underlined the duty of the State to investigate cases of enforced disappearance.

Note 3

Chile’s current authorities: more determined than their predecessors

Unlike his predecessor in office, the current president of Chile has been much more demanding in the search for the truth about the events of September 11, 1973 in Chile.

Last August 30, a Decree was signed in Santiago de Chile to launch a National Search Plan for the still thousands of Chilean citizens who appear on lists of missing persons in Chile (see official communiqué). Since 2013, a report of the Working Group on Enforced Disappearances on Chile recommended this (see report). It should be recalled that on December 22, 2017, rather belatedly and already at the end of her second term, a first initiative had been launched by the then president of Chile (see France24 note of 22/12/2017).

Even in his fourth report (1989), the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Chile, the Costa Rican Fernando Volio Jiménez, referred to the important work that awaited Chilean society in relation to knowing the whereabouts of the victims of forced disappearance (see link to report) (Note 4).

This report by The Guardian published in August 2019 entitled “Where are they?: families search for Chile’s disappeared prisoners” (see link) details in a very complete way the drama of Chilean families in the absence of information about what happened to their loved ones and the lack of political will that meant the arrival in March 2018 of President Piñera regarding the search for missing persons in Chile.

Operation Condor and the right to truth: the inter-American judge’s response to the limited (in?) capacity of the national justice system

Another tragic initiative for Latin America, the so-called “Condor Plan“, in which not only Chile (and the United States) participated, is an area in which many documents have not yet been declassified in the United States: this report by CELS (a reputable NGO in Argentina) explains how this coordinated plan, starting in 1975, worked among the Southern Cone States to erase the protective effect of a threatened person crossing a border between two States.

In its report delivered in December 2014, the Brazilian Truth Commission refers in a much more detailed way than previous truth commissions in its chapter 6 (see text) the level of involvement of the Brazilian military authorities of the time. In this very complete official document published in Uruguay entitled “Participación uruguaya en la coordinación represiva regional. Operation Condor“, analyzes the involvement of Uruguayan authorities.

There are many initiatives to complete and document the modus operandi of the Condor Plan, such as this research project of the University of Oxford (see link) that centralizes a large amount of data.

It should be recalled that it was only in 2016 that the Condor Plan was the subject of a first conviction decision by the Argentine criminal justice system, with respect to high-ranking Argentine military commanders, several of them nonagenarians at the time the sentence was heard (Note 5). Upon learning of this decision by the Argentine justice system, the aforementioned American research program of George Washington University published this note, pointing out that the files declassified by the United States were used by the Argentine judges as documentary evidence.

Chilean military coup

As of 2023, the judicial systems in the Southern Cone are still processing cases of victims and victims’ relatives: this link shows some of the legal actions before national courts related to the Condor Plan.

Given the resistance of some national judges to investigate and punish acts related to the Condor Plan, and the legal maneuvers of all kinds that the lawyers of those responsible for these acts sometimes manage to devise, the Inter-American system for the protection of human rights has offered (and continues to offer) the victims a possibility of obtaining justice.

It is considered that the first judgment of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights to examine the case of a victim of Plan Condor is from 2006 (case Goiburú et al. v. Paraguay).

In another important sentence of the Inter-American judge in 2011 (Gelman vs. Uruguay case) it is stated that:

51. The Condor plan operated in three main areas, namely, first, in political surveillance activities of exiled dissidents or refugees; second, in the operation of covert counter-insurgency actions, in which the role of the actors was completely confidential; and third, in joint extermination actions, aimed at specific groups or individuals, for which special teams of assassins were formed to operate inside and outside the borders of their countries, including in the United States and Europe.

52. This operation was very sophisticated and organized, with constant training, advanced communication systems, intelligence and strategic planning centers, as well as a parallel system of clandestine prisons and torture centers for the purpose of receiving foreign prisoners detained in the framework of Operation Condor.

In its judgment against Argentina 10 years later, in September 2021 (Julien Grisonas family vs. Argentina case), the Inter-American Court of Human Rights stated that this “interstate criminal plan” now merits another coordinated effort by its members, specifying that:

288. In accordance with the requests made, the Court orders the Argentine State, within one year of notification of this judgment and through the channels it deems appropriate, to take the necessary steps to summon the other States that were allegedly involved in the execution of the facts of the case: the Oriental Republic of Uruguay and the Republic of Chile, and, in general, in the context of “Operation Condor”, that is, the Federative Republic of Brazil, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, the Republic of Paraguay and the Republic of Peru, in order to form a working group to coordinate the possible efforts to carry out the tasks of investigation, extradition, prosecution and, if appropriate, punishment of those responsible for the serious crimes committed within the framework of the aforementioned inter-State criminal plan. Such coordination shall be reflected in a common work plan between the competent authorities, according to the matter in question, executed in compliance with the applicable national and international legal framework, and with the help of international cooperation and mutual assistance mechanisms. Thus, the coordinated work between the authorities of the different States will have to undertake joint efforts to clarify what happened during “Operation Condor,” as a scenario in which systematic human rights violations were perpetrated, including those that harmed the victims in this case.

It would be of great interest to know whether Argentina has (or has not) succeeded in complying with this point of the judgment after the one-year term has expired, and what are the reasons for its failure to comply with the request made by the Inter-American judge.

France’s military cooperation in Latin America in the 1970s and 1980s: shadows and gloom

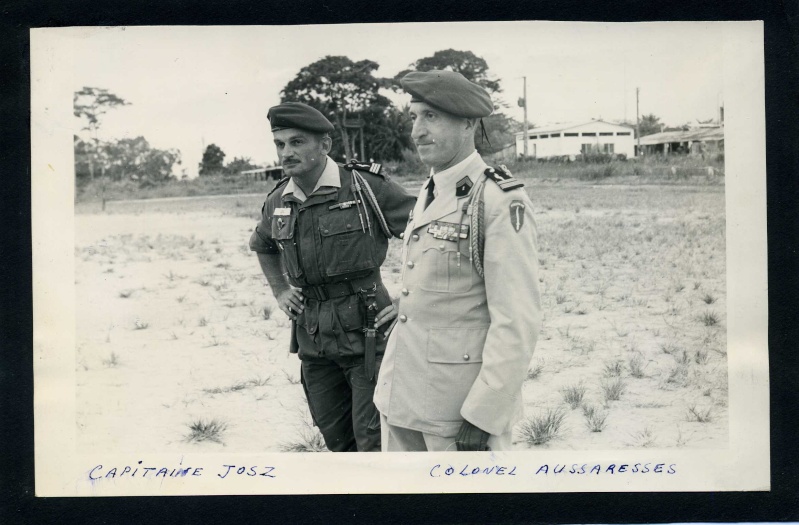

It is of interest to specify with regard to the exact origin of the “technique” of enforced disappearance by military commanders, that recent research in France (see proceedings of specialized forum and article of 2022) shows that it was initiated by French military in Algeria at the end of the 1950s.

A 2003 report broadcast in France, entitled “Escadrons de la mort: l’école française ” (see link as well as short clip on YouTube as well as Part I available here and Part 2 here) gathers several testimonies indicating that French military instructors “taught” in the 70s-80s in military academies of the Southern Cone this “technique” developed by France during the so-called “Guerre d’Algérie“.

In September 2005, the adoption of the draft international convention on enforced disappearances, whose negotiations were chaired at the United Nations headquarters in Geneva by France, reads as follows:

le représentant permanent de la France, l’Ambassadeur Bernard Kessedjian – conclut en ces termes : « Un triple Non a été affirmé ici : Non au silence, Non à l’oubli, Non à l’impunité ! ».

Note 6

In conclusion

Despite the 50 years that separate us from that fateful day for Chile and for the world that September 11, 1973 meant, many questions still persist in time: the United States could usefully clarify them by releasing all the classified documents it still has in its secret archives regarding what happened in Chile. Not to mention the documents it also still has regarding the aforementioned “interstate criminal plan” as the inter-American judge described it.

As for France, its military cooperation in Latin America in the 1970s-1980s would merit a better understanding, based on archives that are probably kept under reserve within the French state apparatus. In September 2003, a “proposition de résolution” along these lines was presented by several French deputies (see full text), without further development.

For the Chilean victims and their families who continue to pursue the truth through time, and seek to know the fate of their loved ones, from Chile or abroad, their exhausting struggle is exemplary: it has inspired, inspires and will continue to inspire, we are sure, many families and several generations of Latin America and the world in their demand for truth and justice.

Chilean military coup

Nicolás Boeglin, in collaboration with Sensorial Sunsets

If you want to read more about this topic, this article might interest you: Memory and Exile in Costa Rica: 50 years after the Military Coup (sensorialsunsets.com).

Notes

Note 1: See GONZALEZ-SALZBERG D.A., “El derecho a la verdad en situaciones de post-conflicto bélico de carácter no internacional“, Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, No.12 (2008), pp. 435-468. Full text available here.

Note 2: See in this regard BOEGLIN N., “JusticiA con A de Ascensión: a propósito de la exhumación de una fosa española a solicitud de una jueza de Argentina“, Revista de Pensamiento Penal, 2016. Text available here.

Note 3: See Colombian Commission of Jurists (CCJ), Derecho a la verdad y derecho internacional, Bogota, 2012, p. 23. Complete work available here.

Note 4: On the close relationship between the right to truth and victims of enforced disappearance, see FERRER MAC-GREGOR E. & GONGORA MAAS J.J., Desaparición forzada de personas y derecho a la verdad en el sistema interamericano de derechos humanos, UNAM/IIJ/CNDH, Mexico 2019. Full text available here.

Note 5: See in this regard BOEGLIN N., “Plan Condor: la justicia argentina se pronuncia“, DerechoalDia legal site, edition of 6/06/2016, text available here.

Nota 6: See DE FROUVILLE O., “La Convention des Nations Unies pour la protection de toutes les personnes contre les disparitions forcées : les enjeux juridiques d’une négociation exemplaire“, Collección Droits Fondamentaux, Número 6, 2006, página 1. Full text of the article available here. A similar reference can be found in TAXIL B., “À la confluence des droits : la convention internationale pour la protection de toutes les personnes contre les disparitions forcées“, Vol. 53, Annuaire Français de Droit International / AFDI (2007) pp. 129-156, p. 129. Full text of the article available here.

Navigate articles